|

Aus dem Inhalt:

Ode to the Westwind

O wild West Wind,

thou breath of Autumn's being,

Thou, from whose

unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like

ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,

Yellow, and black,

and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken

multitudes: O thou,

Who chariotest to

their dark wintry bed

The winged seeds,

where they lie cold and low,

Each like a corpse

within its grave, until

Thine azure sister

of the Spring shall blow

Her clarion o'er

the dreaming earth, and fill

(Driving sweet buds

like flocks to feed in air)

With living hues

and odours plain and hill:

Wild Spirit, which

art moving everywhere;

Destroyer and preserver;

hear, oh, hear!

Thou on whose stream,

mid the steep sky's commotion,

Loose clouds like

earth's decaying leaves are shed,

Shook from the tangled

boughs of Heaven and Ocean,

Angels of rain and

lightning: there are spread

On the blue surface

of thine aery surge,

Like the bright

hair uplifted from the head

Of some fierce Maenad,

even from the dim verge

Of the horizon to

the zenith's height,

The locks of the

approaching storm. Thou dirge

Of the dying year,

to which this closing night

Will be the dome

of a vast sepulchre,

Vaulted with all

thy congregated might

Of vapours, from

whose solid atmosphere

Black rain, and

fire, and hail will burst: oh, hear!

Thou who didst waken

from his summer dreams

The blue Mediterranean,

where he lay,

Lulled by the coil

of his crystalline streams,

Beside a pumice isle

in Baiae's bay,

And saw in sleep

old palaces and towers

Quivering within

the wave's intenser day,

All overgrown with

azure moss and flowers

So sweet, the sense

faints picturing them! Thou

For whose path the

Atlantic's level powers

Cleave themselves

into chasms, while far below

The sea-blooms and

the oozy woods which wear

The sapless foliage

of the ocean, know

Thy voice, and suddenly

grow gray with fear,

And tremble and

despoil themselves: oh, hear!

If I were a dead

leaf thou mightest bear;

If I were a swift

cloud to fly with thee;

A wave to pant beneath

thy power, and share

The impulse of thy

strength, only less free

Than thou, O uncontrollable!

If even

I were as in my

boyhood, and could be

The comrade of thy

wanderings over Heaven,

As then, when to

outstrip thy skiey speed

Scarce seemed a

vision; I would ne'er have striven

As thus with thee

in prayer in my sore need.

Oh, lift me as a

wave, a leaf, a cloud!

I fall upon the

thorns of life! I bleed!

A heavy weight of

hours has chained and bowed

One too like thee:

tameless, and swift, and proud.

Make me thy lyre,

even as the forest is:

What if my leaves

are falling like its own!

The tumult of thy

mighty harmonies

Will take from both

a deep, autumnal tone,

Sweet though in

sadness. Be thou, Spirit fierce,

My spirit! Be thou

me, impetuous one!

Drive my dead thoughts

over the universe

Like withered leaves

to quicken a new birth!

And, by the incantation

of this verse,

Scatter, as from

an unextinguished hearth

Ashes and sparks,

my words among mankind!

Be through my lips

to unawakened earth

The trumpet of a

prophecy! O, Wind,

If Winter comes,

can Spring be far behind? - Percy Bysshe Shelley

Ode an den Westwind

O wilder Westwind,

du des Herbstes Lied,

Vor dessen unsichtbarem

Hauch das Blatt,

Dem Schemen gleich,

der vor dem Zaubrer flieht,

Fahl, pestergriffen,

hektisch rot und matt,

Ein totes Laub,

zur Erde fällt! O du,

Der zu der winterlichen

Ruhestatt

Die Saaten führt

die Scholle deckt sie zu,

Da liegen sie wie

Leichen starr und kalt,

Bis deine Frühlingsschwester

aus der Ruh'

Die träumenden

Gefilde weckt, und bald

Die auferstandnen

Keim' in Blüten sich

Verwandeln, denen

süßer Duft entwallt:

Allgegenwärt'ger

Geist, ich rufe dich,

Zerstörer und

Erhalter, höre mich!

Du, dessen Strömung

bei des Wetters Groll

Die Wolken von des

Himmels Luftgezweig

(Engel von Blitz

und Regen sind es) toll

Wie sinkend Laub

zur Erde schüttelt: gleich

Dem schwarzen Haare,

das man flattern sieht

Um ein Mänadenhaupt,

ist wild und reich,

Vom Saum des Horizonts

bis zum Zenit

Auf deinem Azurfeld

die Lockenpracht

Des nahnden Sturms

verstreut! Du Klagelied

Des sterbenden Jahres,

welchem diese Nacht

Als Kuppel eines

weiten Grabes sich

Gewölbt mit

all der aufgethürmten Macht

Von Dampf und Dunst,

die bald sich prächtiglich

Als Regen, Blitz

entladen: höre mich!

Du, der geweckt aus

seinem Sommertraum

Das blaue Mittelmeer,

das schlummernd lag,

Gewiegt an einer

Bimsstein-Insel Schaum

In Bajä's Bucht

von sanftem Wellenschlag,

Und tief im Schlaf

die Wunderstadt gesehn,

Erglänzend

in der Fluth kristallnem Tag,

Wo blaues Moos und

helle Blumen stehn,

So schön, wie

nimmer sie ein Dichter schuf!

Du, dem im Zorne

selbst entfesselt gehen

Des Weltmeers Wogen,

wenn sie trat dein Huf,

Indeß der

schlammige Wald, der saftlos sich

Das Blatt am Grunde

fristet, deinen Ruf

Vernahm, daß

falb sein grünes Haar erblich

Und er sich bebend

neigte: höre mich!

Wär' ich ein

totes Blatt, von dir entführt,

Wär' eine Wolke,

ziehnd auf deiner Spur,

Wär' eine Welle,

die den Odem spürt

Von deiner Kraft,

und selbst sie teilte, nur

So frei nicht, Stürmender,

wie du! Ja, schritt'

Ich noch, ein Knabe,

auf der Kindheit Flur,

Begleiter dir auf

deinem Wolkenritt,

Als deinen Flug

zu überholen, mir

So leicht erschien:

dann klagt' ich, was ich litt,

So bitter flehend

nicht wie heute dir.

O nimm mich auf,

als Blatt, als Welle bloß!

Ich fall' auf Schwerter

ich verblute hier!

Zu Tode wund sinkt

in des Unmuths Schooß

Ein Geist wie du,

stolz, wild und fessellos.

Lass gleich dem Wald

mich deine Harfe sein,

Ob auch wie seins

mein Blatt zur Erde fällt!

Der Hauch von deinen

mächt'gen Melodein

Macht, dass ein Herbstton

beiden tief entschwellt,

Süß,

ob in Trauer. Sei du, stolzer Geist,

Mein Geist! Sei

ich, du stürmevoller Held!

Gleich welkem Laub,

das neuen Lenz verheißt,

Weh meine Grabgedanken

durch das All,

Und bei dem Liede,

das mich aufwärts reißt,

Streu, wie vom Herde

glühnder Funkenfall

Und Asche stiebt,

mein Wort ins Land hinein!

Dem Erdkreis sei

durch meiner Stimme Schall

Der Prophezeiung

Horn! O Wind, stimm ein:

Wenn Winter naht,

kann fern der Frühling sein? - Percy Bysshe Shelley

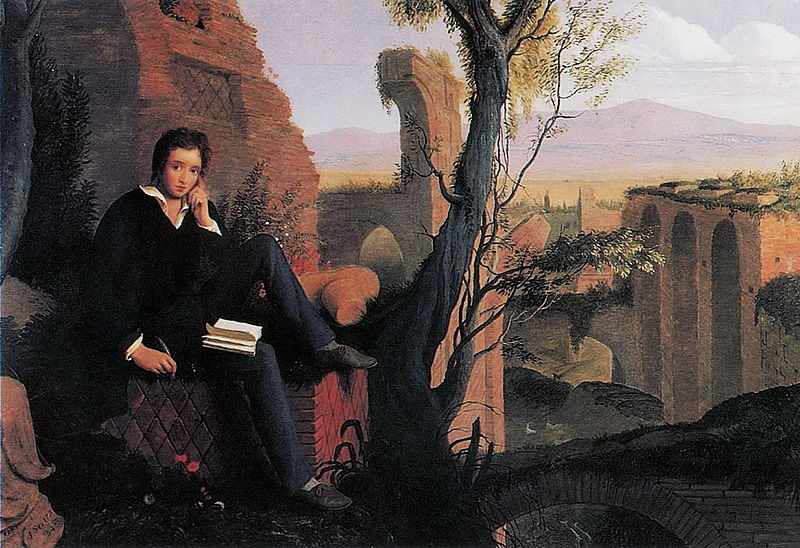

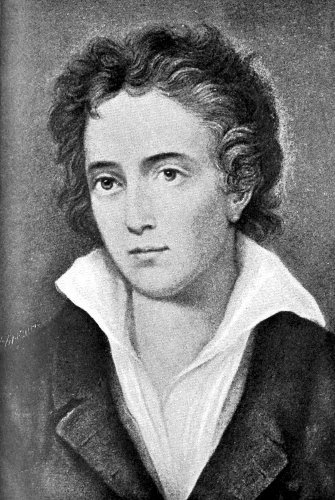

Ähnlich wie

Lord Byron, Goethe, Schiller, Victor Hugo und andere Dichter und Komponisten,

hat auch Percy Bysshe Shelley mit Gedichten wie Epipsychidion und "The

Revolt of Islam - a Poem in twelve Cantos" einen Beitrag zum Philhellenismus

geleistet, der mit Ausbruch des griechischen Unabhängigkeitskrieges

1821 in Europa sich ausbreitete. Percy Bysshe Shelley wurde am 4.

August 1792 in Field Place, Sussex geboren und starb am 8. Juli 1822 bei

einem Segelunfall vor der Küste der Toskana. Er war ein britischer

Schriftsteller, verheiratet mit Mary Wollstonecraft-Shelley. [1]

Mit seinem Werk "The

Revolt of Islam - a Poem in twelve Cantos" zeigt er am Beispiel des griechischen

Freiheitskampfes gegen die Türken und damit gegen den Islam, wie auch

andere islamische Länder das Joch des Islam abschütteln können.

In seinem Vorwort schreibt er: "The Poem which I now present to the

world is an attempt from which I scarcely dare to expect success, and in

which a writer of established fame might fail without disgrace. It is an

experiment on the temper of the public mind, as to how far a thirst for

a happier condition of moral and political society survives, among the

enlightened and refined, the tempests which have shaken the age in which

we live. I have sought to enlist the harmony of metrical language, the

ethereal combinations of the fancy, the rapid and subtle transitions of

human passion, all those elements which essentially compose a Poem, in

the cause of a liberal and comprehensive morality; and in the view of kindling

within the bosoms of my readers a virtuous enthusiasm for those doctrines

of liberty and justice, that faith and hope in something good, which neither

violence nor misrepresentation nor prejudice can ever totally extinguish

among mankind." [2]

Die verdunkelte Orientsonne;

Hydra-Brut

Es geht um das Erwachen

einer "ungeheuren Nation aus ihrer Sklaverei und ein wahres Gefühl

von moralischer Würde und Freiheit" , um die "Enthüllung der

religiösen Betrügereien" des Islams, "durch die sie zur Unterwerfung

getäuscht worden waren." Es geht um wahre Philanthropie, "Verrat und

Barbarei", die "Ungläubigkeit der Tyrannen", also der Sultane, um

die Folgen des islamischen Despotismus, "Bürgerkrieg, Hungersnot,

Pest, Aberglaube", die vergängliche Natur der Unwissenheit und

des Irrtums im Islam und die Ewigkeit des Genies und der Tugend: "For this

purpose I have chosen a story of human passion in its most universal character,

diversified with moving and romantic adventures, and appealing, in contempt

of all artificial opinions or institutions, to the common sympathies of

every human breast. I have made no attempt to recommend the motives which

I would substitute for those at present governing mankind, by methodical

and systematic argument. I would only awaken the feelings, so that the

reader should see the beauty of true virtue, and be incited to those inquiries

which have led to my moral and political creed, and that of some of the

sublimest intellects in the world. The Poem therefore (with the exception

of the first canto, which is purely introductory) is narrative, not didactic.

It is a succession of pictures illustrating the growth and progress of

individual mind aspiring after excellence, and devoted to the love of mankind;

its influence in refining and making pure the most daring and uncommon

impulses of the imagination, the understanding, and the senses; its impatience

at 'all the oppressions which are done under the sun;' its tendency to

awaken public hope, and to enlighten and improve mankind; the rapid effects

of the application of that tendency; the awakening of an immense nation

from their slavery and degradation to a true sense of moral dignity and

freedom; the bloodless dethronement of their oppressors, and the unveiling

of the religious frauds by which they had been deluded into submission;

the tranquillity of successful patriotism, and the universal toleration

and benevolence of true philanthropy; the treachery and barbarity of hired

soldiers; ... the consequences of legitimate despotism,--civil war, famine,

plague, superstition, and an utter extinction of the domestic affections;

the judicial murder of the advocates of Liberty; the temporary triumph

of oppression, that secure earnest of its final and inevitable fall; the

transient nature of ignorance and error and the eternity of genius and

virtue. Such is the series of delineations of which the Poem consists.

[3]

Das "hoffnungslose

Erbe der Unwissenheit und des Elends" wie das Joch des Islams auch bezeichnet

wird, weil ein Volk von Männern und Sklaven "seit Jahrhunderten unfähig

waren, sich selbst mit der Weisheit und Ruhe der Freien" als Staat zu begreifen.

Ihr Verhalten zeigt sich durch keine anderen Zeichen als "Wildheit und

Gedankenlosigkeit", eine historische Tatsache, dessen schlimmsten Merkmale

"Deformität der Freiheit" und "Unwahrheiten" sind. [4]

Zu seinem Stil sagt

Percy B. Shelley: "I do not presume to enter into competition with our

greatest contemporary Poets. Yet I am unwilling to tread in the footsteps

of any who have preceded me. I have sought to avoid the imitation of any

style of language or versification peculiar to the original minds of which

it is the character; designing that, even if what I have produced be worthless,

it should still be properly my own. Nor have I permitted any system relating

to mere words to divert the attention of the reader, from whatever interest

I may have succeeded in creating, to my own ingenuity in contriving to

disgust them according to the rules of criticism. I have simply clothed

my thoughts in what appeared to me the most obvious and appropriate language.

A person familiar with nature, and with the most celebrated productions

of the human mind, can scarcely err in following the instinct, with respect

to selection of language, produced by that familiarity. [5]

Es war zu der Zeit,

"als Griechenland in Gefangenschaft geführt wurde", eine Vielzahl

von syrischen Gefangenen, bigotte zur Anbetung ihres obszönen Aschtaroths

und der unwürdige Nachfolger von Sokrates und Zeno, fanden dort ein

prekäres Existenzminimum: "It was at the period when Greece was led

captive and Asia made tributary to the Republic, fast verging itself to

slavery and ruin, that a multitude of Syrian captives, bigoted to the worship

of their obscene Ashtaroth, and the unworthy successors of Socrates

and Zeno, found there a precarious subsistence by administering, under

the name of freedmen, to the vices and vanities of the great. These wretched

men were skilled to plead, with a superficial but plausible set of sophisms,

in favour of that." [6]

Die Natur deutet

schon auf das, was in den nächsten Szenen bzw Liedern behandelt wird.

Nebel kam auf, der "die Orientsonne in den Schatten stellte:--kein Klang

wurde gehört; eine schreckliche Ruhe hielt die Wälder und die

Fluten und überall Dunkelheit, mehr Furcht als Nacht wurde auf den

Boden gegossen." [7]

Aber "dann stand

Griechenland auf" und seine Barden und Weisen ermunterten die Griechen,

"auch dort, wo sie in der Nacht der Zeitalter schliefen, Ihre Herzen in

die göttlichste Flamme sausen, welcher Atem entzündete, Macht

des heiligsten Namens!" Ihr sonnenähnlicher Ruhm leuchtete nach dem

Kampf, "ein Licht zu retten, wie das Paradies sich über das schattige

Grab ausbreitet. (a light to save, / Like Paradise spread forth beyond

the shadowy grave)" [8]

So ist nun einmal

dieser Konflikt, wenn die Menschheit mit "seinen Unterdrückern in

einem Blutskampf", oder wenn freie Gedanken, wie Blitze, lebendig sind,

und in jedem Busen der Menge Gerechtigkeit und Wahrheit mit der hydra-Brut

des Islam in stillem Krieg sind: "Such is this conflict--when mankind doth

strive / With its oppressors in a strife of blood, / Or when free thoughts,

like lightnings, are alive, / And in each bosom of the multitude / Justice

and truth with Custom's hydra brood." [9]

Es geht um "ein freies

und glückliches Waisenkind". Es treifte es umher am Meer, in einem

tiefen Berg, und in der Nähe der Wellen, und durch die Wälder

wild. Es war ruhig, während der Sturm den Himmel erschütterte:

"Aber als der atemlose Himmel in Schönheit lächelte, weinte ich,

süße Tränen (But when the breathless heavens in beauty

smiled, / I wept, sweet tears." Das Waisenkind ging zwischen den Sterbenden

und den Toten, es ruhte "wie ein Engel in der Drachenhöhle" der Osmanen

und trotzte "dem Tod für Freiheit und Wahrheit". [10]

Es ging damals nicht

darum, wie es heute üblich ist, den Islam aufzuteilen in einen "guten"

Islam und einen "schlechten", den der Islamisten, sondern der Islam generell

war das Problem, denn es waren "böse Glaubensbekenntnisse, dessen

Schatten ein Strom von Gift füttert." Es ging um die "Drachenhöhle"

der Osmanen und die "Enthüllung der religiösen Betrügereien"

des Islams, wie sie auch schon verschiedene byzantinische Autoren oder

Cusanus und Thomas von Aquin aufgezeigt hatten. Natürlich gabe es

immer "schwache Historiker" und "falsche Disputanten" auf islamischer Seite,

"die den Ruin verehrten", der durch den Islam entstanden war. Islamische

oder islamfreundliche Chronisten, die auch heute die Medien verunsichern,

waren bekannt wegen ihrer Geschichtsklitterung. Auch Politiker glaubten

daran. "Schmeichelhafte Macht hatte seine Minister gegeben, ein Thron des

Gerichts im Grab." [11]

Alle "wetteiferten

Im Bösen, Sklave und Despot". Eine seltsame Gemeinschaft hatte sich

in der islamischen Gesellschaft gebildet "durch gegenseitigen Hass" wie

zwei dunkle Schlangen, die sich im Staub verhedderten, und die auf den

Pfaden der Menschen das Gift streuen: "Strange fellowship through mutual

hate had tied, / Like two dark serpents tangled in the dust, / Which on

the paths of men their mingling poison thrust." [12]

Islamische Symbole

wie Halbmond und Venus, Minarette, Moscheen, also "alle Symbole der bösen

Dinge" werden in islamischen Gesellschaften alle als "göttlich" bezeichnet.

Weitere Merkmale islamischer Staaten sind: "Hungersnot", "trostloses

Wehklagen" der verfolgten christlichen Mütter. Shelley schreibt über

die Länder, die vom Islam beherrscht werden: "So trauerte Cythna mit

mir wegen der Knechtschaft, in dem die Hälfte der Menschheit maunzte,

Opfer von Lust und Hass, Sklaven der Sklaven, Sie trauerte darum, dass

Gnade und Macht als Nahrung geworfen wurden an die Hyänenlust, die

unter den Gräbern über dasn verabscheuungswürdige Essen,

lachend in Agonie, toben (Thus, Cythna mourned with me the servitude /

In which the half of humankind were mewed / Victims of lust and hate, the

slaves of slaves, / She mourned that grace and power were thrown as food

/ To the hyena lust, who, among graves, / Over his loathed meal, laughing

in agony, raves." [13]

Licht der Freiheit (light

of deliverance); starker Geist, Ministrant des Guten (strong spirit, ministrant

of good)

Was zeichnet die wahren

Widerstandkämpfer aus? Dazu Shelley: "In mir ist die Gemeinschaft

mit diesem reinsten Wesen, entfachter intensiver Eifer, und machte mich

weise im Wissen, das, sich in meinem eigenen Geist spiegelt, das in der

menschlichen Welt wenige Geheimnisse zurücklässt: Wie ohne Angst

vor dem Bösen oder der Verstellung war Cythna!--was für ein Geist,

stark und mild, welcher Tod, Schmerz oder Gefahr verachtet, ... was für

ein Genie, wild doch mächtig, war es in einem einfachen Kind eingeschlossen!

(In me, communion with this purest being / Kindled intenser zeal, and made

me wise / In knowledge, which, in hers mine own mind seeing, / Left in

the human world few mysteries: / How without fear of evil or disguise /

Was Cythna!--what a spirit strong and mild, / Which death, or pain or peril

could despise, / Yet melt in tenderness! what genius wild / Yet mighty,

was enclosed within one simple child!)" [14]

Mann und Frau müssen

beide frei und gleich behandelt werden, und nicht wie bei den Türken,

die Frauen wie Pferde halten (Lord Byron). Solange werden die islamischen

Gesellschaften mit der Welt unversöhnt sein, "Niemals werden Frieden

und menschliche Natur aufeinandertreffen, bis frei und gleich Mann und

Frau grüßen im Hausfrieden; und ehe diese den Herzen der Menschen

ihren ruhigen und heiligen Sitz erhält, Muss diese Sklaverei gebrochen

werden' - Als ich geredet, aus Cythnas Augen ein Licht des Jubels brach

hervor (Well with the world art thou unreconciled; / Never will peace and

human nature meet / Till free and equal man and woman greet / Domestic

peace; and ere this power can make / In human hearts its calm and holy

seat, / This slavery must be broken'--as I spake, / From Cythna's eyes

a light of exultation brake." [14]

Shelley: "Kann der

Mann frei sein, wenn eine Frau eine Sklavin ist? (Can man be free if woman

be a slave?). Wohl kaum. Sowohl für die Sklavenseelen der Türken

als auch für die Unterdrückten ist es schwierig, gegen das Joch

des Islams anzukämpfen: "Können die, deren Gesellen Tiere sind,

verurteilt zur Verachtung, schwerer als Mühe oder Angst, wagen ihre

Unterdrücker mit Füßen zu treten? (Can they whose mates

are beasts, condemned to bear / Scorn, heavier far than toil or anguish,

dare / To trample their oppressors?)" [15]

Es braucht mehr vom

Schlage einer Cythna, die den Islam, also die "dunkle Falschheit zu entwaffnen"

vermögen. Denn für Kinder wie Cythna gilt immer "Wahrheit hat

seine strahlende Marke als unverwundbaren Charme, auf der Stirn ihrer Kinder

fixiert, die dunkle Falschheit zu entwaffnen (Thy Cythna ever--truth its

radiant stamp / Has fixed, as an invulnerable charm, / Upon her children's

brow, dark Falsehood to disarm." [16]

Langfristig kann

die Freiheit nicht unterdrückt werden, was sich an den islamischen

Revolutionen in den arabischen Ländern zeigt, allerdings gibt es das

"Licht der Freiheit (light of deliverance)" nur außerhalb des Islams.

"And, multitudinous as the desert sand / Borne on the storm, its millions

shall advance, / Thronging round thee, the light of their deliverance."

[17]

Die Bekämpfung

des Islam muss also die Hauptaufgabe bleiben, auch wenn zwischenzeitlich

einige Menschen vor der Unterdrückung der islamischen Tyrannen fliehen

müssen so wie Shelley es beschreibt: "Die Szene wurde verändert,

und weg, weg, weg! Durch die Luft und über das Meer flohen wir, und

Cythna in meinem schützenden Busen lag, ... die klaffende Erde dann

erbrach Legionen von üblen und schrecklichen Formen, die hingen auf

meinem Flug; und immer, als wir flohen, zupften sie an Cythna - bald

an mir ... atemlos, blass und ahnungslos stieg ich, und alle Hütten

überfüllt gefunden mit bewaffneten Männern, deren glitzernde

Schwerter nackt waren, und deren degradierte Gliedmaßen das

Gewand des Tyrannen trugen (The scene was changed, and away, away, away!

/ Through the air and over the sea we sped, / And Cythna in my sheltering

bosom lay, / ... the gaping earth then vomited / Legions of foul

and ghastly shapes, which hung / Upon my flight; and ever, as we fled,

/ They plucked at Cythna--soon to me then clung." /... breathless,

pale and unaware / I rose, and all the cottage crowded found / With armed

men, whose glittering swords were bare, / And whose degraded limbs the

tyrant's garb did wear." [18]

Die osmanisch-islamischen

Soldaten, "diese blutigen Männer sind nur die Sklaven", deren Aufgabe

es war, andere in die Sklaverei hineinzuziehen, das Schicksal zu teilen,

und unter den Gefangenen bereit sein Ketten zu tragen, verheerten ganze

Landstriche: "In der Ebene tobte die Schlacht,--wälzte sich über

/ Die Weinberge und die Ernten, und die Glut / Von brennenden Dächern

leuchtete weit .. (These bloody men are but the slaves who bear /

Their mistress to her task--it was my scope / The slavery where they drag

me now, to share, / And among captives willing chains to wear." / ... The

plain was filled with slaughter,--overthrown / The vineyards and the harvests,

and the glow / Of blazing roofs shone far o'er the white Ocean's flow."

[19]

Die Griechen freuten

sich natürlich, wenn sie aus der türkischen Gefangenschaft befreit

wurden: "Though he said little, did he speak to me. / 'It is a friend beside

thee--take good cheer, / Poor victim, thou art now at liberty!' / I joyed

as those a human tone to hear, / Who in cells deep and lone have languished

many a year." [20]

Ein "starker Geist,

Ministrant des Guten", weise und gerecht, der Blick gegen die Lästerer

des Geistes "so scharf wie der Blitzschlag"; der Heiland, beschützt

und heilt die christlichen Griechen - ein Vorteil, der den im islamischen

Joch gefangenen Moslems nicht zukommt: "Als ich geheilt wurde, führte

er mich hinaus, um die Wunder seiner sylvanischen Einsamkeit zu zeigen,

und wir saßen zusammen bei dieser inselfressenden Flut. (Like a strong

spirit ministrant of good: / When I was healed, he led me forth to show

/ The wonders of his sylvan solitude, / And we together sate by that isle-fretted

flood. / ... Of wisdom and of justice when he spoke-- / When mid soft looks

of pity, there would dart / A glance as keen as is the lightning's stroke

/ When it doth rive the knots of some ancestral oak.)" [21]

Die unverdorbene

Jugend schöpft noch aus dem Geist: "Ja, aus den Aufzeichnungen meines

jugendlichen Zustands, und aus der Geschichte der Barden und alten Weisen,

erstelle ich meine Gedanken, habe ich Sprache gesammelt, um

Wahrheit für

meine Landsleute darzulegen (Yes, from the records of my youthful state,

/ And from the lore of bards and sages old, / From whatsoe'er my wakened

thoughts create / Out of the hopes of thine aspirings bold, / Have I collected

language to unfold / Truth to my countrymen; from shore to shore." [22]

Nur dieser Geist

bringt "die Tyrannen der Goldenen Stadt" zum zittern; gegen die Wahrheit

kommen auch ihre "Betrugsminister" mit den "Lügen ihres eigenen Herzens"

nicht an; auch die Richter an islamischen Gerichten (Scharia), die das

Recht verfälschen - Shelley nennt sie Mörder auf Richtersitzen:

"Mörder sind blass auf den Richtersitzen" - können gegen die

Wahrheit nichts ausrichten: "The tyrants of the Golden City tremble / At

voices which are heard about the streets; /

The ministers of

fraud can scarce dissemble / The lies of their own heart, ... / Murderers

are pale upon the judgement-seats." [23]

Dieser Geist, die

"Macht des Guten" , siegt immer, auch "durch das Labyrinth von vielen

Zelten, unter den stillen Millionen, die lügen." Diejenigen, die diesen

Geist der Freiheit teilen, jubeln und erkennen sich überall: "And

now the Power of Good held victory. / So, through the labyrinth of many

a tent, / Among the silent millions who did lie / In innocent sleep, exultingly

I went; / The moon had left Heaven desert now, but lent / From eastern

morn the first faint lustre showed / An armed youth--over his spear he

bent / His downward face.--'A friend!' I cried aloud, / And quickly common

hopes made freemen understood." [24]

Vor dem Geist der

Freiheit flohen die Türken: "In plötzlicher Panik flohen die

falschen Mörder, / Wie Insektenstämme vor dem Nordsturm (In sudden

panic those false murderers fled, / Like insect tribes before the northern

gale." [25]

Alle Griechen, durchdrungen

von dem Licht des "großen Geistes", feierten die Besieger der Türken

in einer lauten Symphonie: "Der Freund und der Bewahrer des Freien! Der

Elternteil dieser Freude! (And they, and all, in one loud symphony / My

name with Liberty commingling, lifted, / 'The friend and the preserver

of the free! / The parent of this joy!' and fair eyes gifted / With feelings,

caught from one who had uplifted / The light of a great spirit, round me

shone; / And all the shapes of this grand scenery shifted / Like restless

clouds before the steadfast sun" [26]

Und der Gipfel leuchtete

wie Athos von Samothraki aus gesehen

Die Türken, oft

als Mörder verschrien, hatten in allen eroberten Ländern "Hungersnot

oder Pest" verbreitet. Daher war die Freude groß, wenn der Unterdrücker

besiegt und wieder fort war und man tat alles, damit er nicht zurückkam:

"Und er ist gefallen!" rufen sie, "Er, der wohnte wie Hungersnot oder Pest,

unter unseren Häusern, ist gefallen! der Mörder, der seine durstige

Seele wie aus einem Brunnen von Blut und Tränen ruiniert! er ist hier!

Versunken in einem Golf von Verachtung, aus dem ihn niemand aufziehen darf!'

(Slowly the silence of the multitudes / Passed, as when far is heard in

some lone dell / The gathering of a wind among the woods-- / 'And he is

fallen!' they cry, 'he who did dwell / Like famine or the plague, or aught

more fell / Among our homes, is fallen! the murderer / Who slaked his thirsting

soul as from a well / Of blood and tears with ruin! he is here! / Sunk

in a gulf of scorn from which none may him rear!')" [27]

Schon Ariost hatte

gefragt, warum die Türken alles verpesten dürfen. Auch Shelley

fragt sich: "Sollen die Osmanen (Türken) nur ungerächt plünern?"

Sollen die Griechen weiter unterdrückt werden, und sich für den

Luxus der Türken abmühen? Er fordert die Griechen auf "Steht

auf! Und bringt zur hohen Gerechtigkeit ihr auserwähltes Opfer! (Then

was heard--'He who judged let him be brought / To judgement! blood for

blood cries from the soil / On which his crimes have deep pollution wrought!

/ Shall Ottomans only unavenged despoil? / Shall they who by the stress

of grinding toil / Wrest from the unwilling earth his luxuries, / Perish

for crime, while his foul blood may boil, / Or creep within his veins at

will?--Arise! /

And to high justice

make her chosen sacrifice!')" [28]

Und der Gipfel leuchtete

wie Athos von Samothraki aus gesehen. Die Weisheit thront über allem,

und unter ihren Füßen krümmt sich der Glaube der Ottomanen

und die Torheit, islamisches Brauchtum und Hölle: "die Erde beginnt,

die mächtige Warnung zu hören, von deiner Stimme erhaben und

heilig; seine Freigeister sind hier versammelt, sehen dich, fühlen

dich, kennen Sie jetzt,-- zu deiner Stimme haben ihre Herzen gezittert...

Weisheit! Deine unwiderstehlichen Kinder steigen auf um Sie zu bejubeln,

und die Elemente, die sie verketten und ihr eigener Wille, die Herrlichkeit

deines Zuges anschwellen zu lassen. (... and the summit shone / Like Athos

seen from Samothracia.... / And underneath thy feet writhe Faith, and Folly,

/ Custom, and Hell, and mortal Melancholy-- / Hark! the Earth starts

to hear the mighty warning / Of thy voice sublime and holy; / Its free

spirits here assembled / See thee, feel thee, know thee now,-- / To thy

voice their hearts have trembled / ... Wisdom! thy irresistible children

rise / To hail thee, and the elements they chain / And their own will,

to swell the glory of thy train." [29]

Rache und Egoismus,

wie sie heute in islamischen Gesellschaften herrschen, sind trostlos. Rachegifte

sollen aufgehört haben, Krankheit und Angst und Wahnsinn zu nähren.

"Mitleid und Frieden und Liebe, unter den Guten und Freien!" - das wird

es bei den Osmanen bzw. Türken nicht geben; sie tragen also nicht

dazu bei, "diese Erde, unser Zuhause, schöner zu machen". Erst die

christliche Freiheit kann durch "die Wissenschaft und ihre Schwester Poesie"

die "Felder und Städte der Freien in Licht kleiden!" [30]

'O Spirit

vast and deep as Night and Heaven!

Mother and soul

of all to which is given

The light of life,

the loveliness of being,

Lo! thou dost re-ascend

the human heart,

Thy throne of power,

almighty as thou wert

In dreams of Poets

old grown pale by seeing

The shade of thee;--now,

millions start

To feel thy lightnings

through them burning:

Nature, or God,

or Love, or Pleasure,

Or Sympathy the

sad tears turning

To mutual smiles,

a drainless treasure,

Descends amidst

us;--Scorn and Hate,

Revenge and Selfishness

are desolate--

A hundred nations

swear that there shall be

Pity and Peace and

Love, among the good and free! - Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt of Islam

V

("O Geist weit und

tief wie Nacht und Himmel!

Mutter und Seele

von allem, dem gegeben ist

Das Licht des Lebens,

die Lieblichkeit des Seins,

Lo! Du wirst das

menschliche Herz wieder aufsteigen lassen,

Dein Thron der Macht,

allmächtig wie du

In Träumen

von Dichtern alt geworden und blass durch das Sehen

Der Schatten von

Ihnen;--jetzt, Millionen starten

Um zu spüren,

wie deine Blitze durch sie brennen:

Natur, oder Gott,

oder Liebe oder Vergnügen,

Oder Sympathie die

traurigen Tränen drehen

Zum gegenseitigen

Lächeln, ein unentleerter Schatz,

Steigt inmitten

von uns ab;--Verachtung und Hass,

Rache und Egoismus

sind trostlos--

Hundert Nationen

schwören, dass da sein werden

Mitleid und Frieden

und Liebe, unter den Guten und Freien!)

My brethren, we are

free! The fruits are glowing

Beneath the stars,

and the night-winds are flowing

O'er the ripe corn,

the birds and beasts are dreaming--

Never again may

blood of bird or beast

Stain with its venomous

stream a human feast,

To the pure skies

in accusation steaming;

Avenging poisons

shall have ceased

To feed disease

and fear and madness,

The dwellers of

the earth and air

Shall throng around

our steps in gladness,

Seeking their food

or refuge there.

Our toil from thought

all glorious forms shall cull,

To make this Earth,

our home, more beautiful,

And Science, and

her sister Poesy,

Shall clothe in

light the fields and cities of the free! - Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt

of Islam V

Die Griechen riefen

den verbliebenen islamischen bzw. osmanischen Staaten zu: "Sieg! Sieg!

Der entlegensten Küste der Erde". Könige werden blass werden!

Allmächtige Angst breitet sich unter Moslems aus, "der Satan-Gott

(Allah), wenn er unseren zauberhaften Namen hört, soll verblassen

wie Schatten von seinen tausend Tempeln (Moscheen), während die Wahrheit

mit der Freude inthronisiert wird, herrscht sein verlorenes Imperium! (Victory!

Victory! Earth's remotest shore, / ... Kings shall turn pale! Almighty

Fear, / The Fiend-God, when our charmed name he hear, / Shall fade like

shadow from his thousand fanes, / While Truth with Joy enthroned o'er his

lost empire reigns!')" Übrigens hatte sich der von Shelley verehrte

Torquato Tasso ähnlich geäußert: "Die Mütter ziehn

indes in die Moscheen, um zu dem bösen Lügnergott zu flehen"

[31]

Vorerst liefen noch

"die Bluthunde des Despoten mit ihrer Beute", unbewaffnet und ahnungslos,

um mit lautem Gelächter für ihren Tyrannen zu ernten, eine Ernte,

die mit anderen Hoffnungen gesät wurde, für ihre "Völlerei

des Todes"

"For now the despot's

bloodhounds with their prey / Unarmed and unaware, were gorging deep /

Their gluttony of death; the loose array / Of horsemen o'er the wide fields

murdering sweep, / And with loud laughter for their tyrant reap / A harvest

sown with other hopes)" [32]

Das göttliche

Naturgesetz besagt, dass, wer zusammenwächst, sich nur die Liebe aussuchen

kann - allerdings nur wenn sich der Irrglaube der Osmanen nicht dazwischenstellt,

oder die Sklaverei des Islams. Davon abgesehen handelt es sich um alle

"sanftesten Gedanken, wie im heiligen Hain. (And such is Nature's law divine,

that those / Who grow together cannot choose but love, / If faith or custom

do not interpose, / Or common slavery mar what else might move / All gentlest

thoughts; as in the sacred grove)" [33]

Die osmanischen Soldaten

haben nicht nur in eroberten Ländern Frauen und Kinder abgeschlachtet,

sondern auch im eigenen Land einen Genozid an der christlichen Bevölkerung

verübt; die heutige Türkei existiert nur weil türkische

Soldaten sämtliche Christen entweder abgeschlachtet oder vertrieben

haben. "Es gab ein trostloses Dorf in einem Wald ... es war ein Ort des

Blutes, ... überall lagen Frauen, Babies und Männer durcheinander

abgeschlachtet. (There was a desolate village in a wood ... it was a place

of blood, ... and around did lie Women, and babes, and men, slaughtered

confusedly." [34]

Zudem hatten die

Türken Pest und Hungersnot verbreitet: "Die blauen Küsse der

Pest ... bald werden Millionen die Pest verbreiten ... Mein Name ist Pestilence

... Hungersnot (The Plague's blue kisses--soon millions shall pledge the

draught! ... My name is Pestilence ...Famine)" [35]

Der Geist und Verstand

kann natürlich nur wachsen, wenn eine Verbindung zu Weisheit und Gerechtigkeit,

Wahrheit und Liebe besteht, eine Verbindung die bei den islamischen Osmanen

unterbrochen ist, bei den griechischen Freiheitskämpfern aber fortbesteht:

"Mein Verstand wurde das Buch, durch das ich wuchs, Weise in aller menschlichen

Weisheit ... wie eine Mine, ... Ein Geist, die Art von allem, ... Notwendigkeit

und Liebe und Leben, das Grab, und Sympathie, Brunnen der Hoffnung und

Angst, Gerechtigkeit, Wahrheit und Zeit und die natürliche Sphäre

der Welt." [36]

My mind

became the book through which I grew

Wise in all human

wisdom, and its cave,

Which like a mine

I rifled through and through,

To me the keeping

of its secrets gave--

One mind, the type

of all, the moveless wave

Whose calm reflects

all moving things that are,

Necessity, and love,

and life, the grave,

And sympathy, fountains

of hope and fear,

Justice, and truth,

and time, and the world's natural sphere. - Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt

of Islam VII

Der Pomp der islamischen

Religion wurde "durch die Verachtung eines weisen Lächelns desolat"

und osmanische Throne wurden gestürzt, und "Wohnungen mit milden Menschen

durchsetzt, auf Feldern reifte wieder Mais, (Religion's pomp made desolate

by the scorn / Of Wisdom's faintest smile, and thrones uptorn, / And dwellings

of mild people interspersed / With undivided fields of ripening corn, /

And love made free,--a hope which we have nursed / Even with our blood

and tears)" [37]

Shelley ruft den

islamischen Ländern, die noch unter dem Joch des Islam leben, zu:

"Alles ist nicht verloren! Es gibt etwas Belohnung für die Hoffnung,

deren Brunnen so tiefgründig sein können" , sogar die "Ohnmacht

des Bösen", das osmanische Reich, "seine Hölle der Macht" wird

verspottet durch den "geheimen Klang von Hymnen auf Wahrheit und Freiheit.

('All is not lost! There is some recompense / For hope whose fountain can

be thus profound, / Even throned Evil's splendid impotence, / Girt by its

hell of power, the secret sound / Of hymns to truth and freedom)" [38]

Begraben sind Angst,

der falsche Glaube der Moslems und Sklaverei; das Joch des Islam war abgeschüttelt

und die Menschheit frei. [39]

'Thy songs

were winds whereon I fled at will,

As in a winged chariot,

o'er the plain

Of crystal youth;

and thou wert there to fill

My heart with joy,

and there we sate again

On the gray margin

of the glimmering main,

Happy as then but

wiser far, for we

Smiled on the flowery

grave in which were lain

Fear, Faith and

Slavery; and mankind was free,

Equal, and pure,

and wise, in Wisdom's prophecy. - Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt of Islam

VII

("Deine Lieder waren

Winde, auf die ich nach Belieben floh,

Wie in einem geflügelten

Wagen, o'er die Ebene

Von Kristalljugend;

und du bist da, um zu füllen

Mein Herz mit Freude,

und da sitzen wir wieder

Am grauen Rand des

schimmernden Hauptteils

Glücklich wie

damals, aber klüger, für uns

Lächelt auf

dem blumigen Grab, in dem lagen

Angst, Glaube und

Sklaverei; und die Menschheit war frei,

Gleich und rein

und weise in der Prophezeiung der Weisheit.)

Das Griechische Mittelmeer

mit seinen vielen Inseln ist heute der Traum der Urlauber aus Mittel- und

Nordeuropa. Damals lauerte allerdings immer die Gefahr türkischer

Schiffe. Gegen die Türken muss man kämpfen, "Pest ist kostenlos

(Plague is free)" wie Erdbeben, Hagel und Schnee: "Ihr könnt euch

nicht auf dem tristen Meer ausruhen! Eile, Eile in die warme Heimat

des glücklicheren Schicksals! (Ye cannot rest upon the dreary sea!--

/ Haste, haste to the warm home of happier destiny!)" [40]

Für den Griechen

war der Türke wie "tiefste Hölle" und "todlose Schlange", wie

eine Pest, eine Last und ein Fluch, klammerte der Türke sich an ihn,

während er lebte: "And deepest hell, and deathless snakes among, ...

like a plague, a burden, and a bane, clung to him while he lived." [41]

Die Frau ist durch

die Türken eine Sklavin geworden, Ein Kind der Verachtung, der Ausgestoßene

eines verwüsteten Hauses; Falschheit, Angst und Mühe zeigen sich

wie Kanäle auf ihrer Wange, die das Lächelt schmücken sollte.

[42]

Woman!--she

is his slave, she has become

A thing I weep to

speak--the child of scorn,

The outcast of a

desolated home;

Falsehood, and fear,

and toil, like waves have worn

Channels upon her

cheek, which smiles adorn,

As calm decks the

false Ocean:--well ye know

What Woman is, for

none of Woman born

Can choose but drain

the bitter dregs of woe,

which ever from

the oppressed to the oppressors flow. - Percy Bysshe Shelley,

The Revolt of Islam VIII

Von türkischen

"Eroberern und Betrügern falsch und kühn, die Zwietracht eurer

Herzen, ich in euren Blicken sehe. (Of conquerors and impostors false and

bold, / The discord of your hearts, I in your looks behold)." [43]

The glorious joy of

thy name - Liberty! ; richtiges beten und schwören

Die Griechen geben die

Hoffnung nicht auf, denn die Wahrheit ist in ihrer Seele und ihr Herz ist

nicht durch den Schlangenzahn des Islam verletzt; sie Schwören, "bis

zum Tod fest zu sein!" Schließlich schwören sie nicht bei irgendwelchen

Gegenständen wie Mohammed im Koran, sondern auf Christus. Mit Weisheit

hat es auch nichts zu tun, wenn "sinnlose Schwurformeln" verwendet, Dämonen

als Götter bezeichnet, oder rituelle Waschungen vorgenommen werden,

was nämlich nichts nutzt, "wenn die Seelen der Leute voll Unreinheit

sind"; auch unsinnige Fastenregeln des Ramadan, die dem Moslem erlaubt,

"die ganze Nacht hindurch zu schmausen und ausschweifend zu sein", können

ihn nicht vom "Seelenfressenden" Ungeheuer Allah retten. "Von diesen Eiden",

sagt Muhammad, stammten die einen von Allah persönlich, "andere schwört

er selbst; auch damit verblüfft er die Barabaren und will ihnen zeigen,

dass er vieles weiß und tiefe Geheimnisse kennt." [44]

"In einigen

Fabeln (Suren) bringt er gewisse andere barbarische und sinnlose Schwurformeln,

die seiner Torheit und Verücktheit nicht ermangeln. So wieder an einer

anderen Stelle: 'Bei dem Schreibrohr und dem, was sie zeilenweise niederschreiben"

(Sure 68, 1). Wiederum an einer anderen Stelle bringt er den Schwur: 'Bei

denen, die aus der Reihe gesandt werden, bei den Stürmen der Stürme,

bei den Ausbreitungen des Ausgebreiteten, ... bei

denen, die eine

Mahnung ausstoßen zur Verteidigung' (Sure 77, 1-6). Ferner an einer

anderen Stelle: 'Bei denen, die das Geschoss zurückziehen, die im

Wegnehmen wegnehmen, die im Schwimmen schwimmen, die Vorsprung

gewinnen und die

Angelegenheit regeln am Tag, an dem das Beben bebt' (Sure 79, 1-6). Ferner

in einer anderen Fabel: 'Bei dem mit Türmen befestigten Himmel, bei

dem Tag des Versprechens, bei dem Zeugen und dem

Bezeugten' (Sure

85, 1-3). Ferner in einer anderen: 'Beim Himmel und dem Nachtstern. Wie

kannst du wissen, was der Nachtstern ist? Es ist der durchbohrende Stern'

(Sure 86, 1-3). Ferner in einer anderen: 'Bei der Morgenröte

und zehn Tagen,

bei dem Geraden und dem Ungeraden, bei der Nacht, wenn sie sich ausbreitet'

(Sure 89, 1-4). Ferner in einer anderen: 'Bei den Feigenbäumen und

den Ölbäumen des Sinai und bei dieser Stadt' (Sure 95, 1-3).

Ferner in einer

anderen: 'Bei denen, die keuchend laufen, die Funkenflug bewirken und die

am Morgen einfallen und stehendes Wasser aufwühlen' (Sure 100, 1-4)."

- Euthymios Zigabenos, Panoplia dogmatica, 28

"Er sagt noch vieles

andere von der Art, das schwer auszusprechen und töricht ist und die

Ohren seiner Schüler geißelt. Ferner schwört Muhammad bei

Sonne und Mond, bei den Sternen, bei Feuerglanz, bei Tieren, schnellen

Hunden, Pflanzen

und anderen unbekannten und barbarischen Namen, die, wich ich glaube, irgendwelche

frevelhaften und mörderischen Dämonen bezeichnen. Indem er bei

diesen Namen schwört, zeigt er, dass er sie für Götter

hält.."

- Euthymios Zigabenos, Ib.

"Er befiehlt denen,

die zum Gebet gehen, sich zu reinigen mit Wasser, wenn es vorhanden ist,

wenn es fehlt, mit Erde; aber diese beschmutzt vielmehr und reinigt nicht.

Doch was vermag auch die bloße Reinigung mit Wasser,

wenn die Seelen

der Leute voll Unreinheit sind?" - Euthymios Zigabenos, Ib.

"Bei der Gesetzgebung

über das Fasten sagt erfolgendes: 'Die Nacht der Fastenzeit ist euch

zum Beischlaf mit euren Frauen erlaubt; denn diese sind eure Bekleidung

und ihr seid eine Bekleidung für sie. Denn Gott (Allah) weiß,

dass ihr eure Seelen

betrügt in der Fastenzeit, und er erweist sich euch als gnädig.

Vereinigt euch mit ihnen als Trost und esst am Abend und trinkt, bis der

in der Nacht schwarze Faden durch den Tagesanbruch weiß erscheint.

Darauf erfüllt

wieder das Fastengebot bis zum Abend und vereinigt euch nicht mit ihnen,

sondern verweilet in den Moscheen. Das ist das Gesetz Gottes.' (Sure 2,

181 ff.) Was ist das für ein Fasten, du Unreiner, oder was für

ein

Gesetz Gottes, die

ganze Nacht hindurch zu schmausen und ausschweifend zu sein?" - Euthymios

Zigabenos, Ib.

"Er schrieb vor,

dass jeder von euch vier Frauen nehmen könne, Mätressen aber

tausende oder so viele er unterhalten könne. Die Mätressen sollten

den Frauen untergeordnet sein. Der Mann könne die Frau, die er wolle,

entlassen und eine

andere an ihrer Stelle heiraten (Sure 4, 3). Oh unübertreffliche und

schweinische oder hündische Zuchtlosigkeit!" - Euthymios Zigabenos,

Ib.

"Recede not! pause

not now! Thou art grown old,

But Hope will make

thee young, for Hope and Youth

Are children of

one mother, even Love--behold!

The eternal stars

gaze on us!--is the truth

Within your soul?

care for your own, or ruth

For others' sufferings?

do ye thirst to bear

A heart which not

the serpent Custom's tooth

May violate?--Be

free! and even here,

Swear to be firm

till death!" They cried, "We swear! We swear!" - Percy Bysshe Shelley,

The Revolt of Islam VIII

"Die herrliche Freude

deines Namens - Freiheit!" können natürlich nur Nicht-Muslime

preisen; die "fiebrige Welt" des Islam kennt keine Freiheit. Die "dunkle

Türken-Brut" kennt nur Ängste und Sorgen. [45]

'The many

ships spotting the dark blue deep

With snowy sails,

fled fast as ours came nigh,

In fear and wonder;

and on every steep

Thousands did gaze,

they heard the startling cry,

Like Earth's own

voice lifted unconquerably

To all her children,

the unbounded mirth,

The glorious joy

of thy name--Liberty!

They heard!--As

o'er the mountains of the earth

From peak to peak

leap on the beams of Morning's birth:

'So from that cry

over the boundless hills

Sudden was caught

one universal sound,

Like a volcano's

voice, whose thunder fills

Remotest skies,--such

glorious madness found

A path through human

hearts with stream which drowned

Its struggling fears

and cares, dark Custom's brood;

They knew not whence

it came, but felt around

A wide contagion

poured--they called aloud

On Liberty--that

name lived on the sunny flood. - Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt of Islam

IX

Es geht um "Wahrheit,

Freiheit und Liebe". Sanfte Gedanken der Weisheit erfüllten so manche

Brust, unbesiegbar war der Wille. [46]

'For, with

strong speech I tore the veil that hid

Nature, and Truth,

and Liberty, and Love,--

As one who from

some mountain's pyramid

Points to the unrisen

sun!--the shades approve

His truth, and flee

from every stream and grove.

Thus, gentle thoughts

did many a bosom fill,--

Wisdom, the mail

of tried affections wove

For many a heart,

and tameless scorn of ill,

Thrice steeped in

molten steel the unconquerable will. - Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt

of Islam IX

Die Frauen werden aus

dem Harem der Türken befreit, Ihre vielen Tyrannen sitzen desolat

In "sklavenverlassenen Hallen (slave-deserted halls)". Der Tyrann wusste,

dass seine Macht verschwunden war, aber diese perfide Sitte der Moslems

und die Gewohnheit von Gold und Gebet, "um das Zepter der Welt zu betrügen,...

deshalb sandte er überall die falschen Priester auf die Straßen,

die Imame, um die Rebellen zu verfluchen, beten zu ihren falschen Göttern,

und knien in der Öffentlichkeit." Auch heute findet sogar in Europa

sogenanntes "Schaubeten" der Moslems auf öffentlichen Straßen

und Plätzen statt. [47]

'The Tyrant

knew his power was gone, but Fear,

The nurse of Vengeance,

bade him wait the event--

That perfidy and

custom, gold and prayer,

And whatsoe'er,

when force is impotent,

To fraud the sceptre

of the world has lent,

Might, as he judged,

confirm his failing sway.

Therefore throughout

the streets, the Priests he sent

To curse the rebels.--To

their gods did they

For Earthquake,

Plague, and Want, kneel in the public way. - Percy Bysshe Shelley,

The Revolt of Islam IX

Moslems beten

gerne das Gold als ihren Gott an, z.B. den Felsendom mit goldener Kuppel,

die Kaaba in Mekka mit goldenem Tor, "Denn Gold war wie ein Gott, dessen

Glaube aber zu Verblassen begann", so dass seine Anbeter in Griechenland

weniger wurden, und der islamische Glaube selbst, der im Herzen des Menschen

einen "spektralen Terror" erzeugt, seinem Untergang entgegen ging, als

es einsamer wurde in den Moscheen, bis die Imame allein in der Moschee

standen und ihre "Pfeile der Unwahrheit" verschossen, um Zwietracht in

die "Vereinigung der Freien" zu säen. [48]

'For gold

was as a god whose faith began

To fade, so that

its worshippers were few,

And Faith itself,

which in the heart of man

Gives shape, voice,

name, to spectral Terror, knew

Its downfall, as

the altars lonelier grew,

Till the Priests

stood alone within the fane;

The shafts of falsehood

unpolluting flew,

And the cold sneers

of calumny were vain,

The union of the

free with discord's brand to stain. - Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt

of Islam IX

Das Symbol (Halbmond)

der "wissenschaft der Verschwendung" schwindet in der Dunkelheit. Die verbliebenen

Moslems, "die Söhne der Erde zu ihren üblen Götzen beten,

und graue Priester triumphieren", und wie Plage oder eine Explosion ist

ein Schatten der "egoistischen Fürsorge" vor den menschlichen Blicken

ausgegossen. [49]

The seeds

are sleeping in the soil: meanwhile

The Tyrant peoples

dungeons with his prey,

Pale victims on

the guarded scaffold smile

Because they cannot

speak; and, day by day,

The moon of wasting

Science wanes away

Among her stars,

and in that darkness vast

The sons of earth

to their foul idols pray,

And gray Priests

triumph, and like blight or blast

A shade of selfish

care o'er human looks is cast.- Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt of Islam

IX

Die Guten und Großen

der vergangenen Zeitalter Sind in ihren Gräbern, die Unschuldigen

und Freien, Helden und Dichter und vorherrschende Weisen, Wer kleidet und

schmückt diese nackte Welt [50]

The good

and mighty of departed ages

Are in their graves,

the innocent and free,

Heroes, and Poets,

and prevailing Sages,

Who leave the vesture

of their majesty

To adorn and clothe

this naked world;--and we

Are like to them--such

perish, but they leave

All hope, or love,

or truth, or liberty,

Whose forms their

mighty spirits could conceive,

To be a rule and

law to ages that survive. - Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Revolt of Islam IX

Zeichen des kommenden

Unheils (Signs of the coming mischief)

Später wurde mit

dem "ruchlosen Sultan (foul Tyrant)", der sein Antlitz verräterisch

in Lügen hüllt, ein "Seltsamer Waffenstillstand, mit vielen ritus

(Strange truce, with many a rite)", geschlossen - So wie noch heute seltsame

Waffenruhen mit den Türken ausgehandelt werden. Die Politiker und

die beteiligten Priester, kannten den Sachverhalt und "schworen Wie Wölfe

und Schlangen in ihren gemeinsamen Kriegen (they knew his cause their own,

and swore Like wolves and serpents to their mutual wars)" [51]

Myriaden waren gekommen

- Millionen waren auf dem Weg, Der Sultan (Tyrann) ging vorbei, "umgeben

vom Stahl der angeheuerten Attentäter (islamische Terroristen), durch

den öffentlichen Weg, erstickt mit den Toten seines Landes... - er

lächelt. "Ich bin ein König in Wahrheit!" sagte er und nahm seinen

königlichen Sitz ein, mit Folterrad, Feuer und Zangen und Haken, und

Skorpionen, damit seine Seele auf ihre Rache schauen könnte. (The

Tyrant passed, surrounded by the steel Of hired assassins, through the

public way, Choked with his country's dead:--his footsteps reel On the

fresh blood--he smiles. I am a King in truth!' he said, and took His royal

seat, and bade the torturing wheel Be brought, and fire, and pincers, and

the hook, And scorpions, that his soul on its revenge might look)." [52]

Worin besteht die

Aufgabe des türkischen Sultans? Der Sultan beauftragt seine

islamischen Söldner, zuerst die Rebellen, also christliche Griechen,

zu töten; er hofft dadurch die anderen Griechen zu beschwichtigen

"Noch leben Millionen, Von denen sich die Schwächsten mit einem Wort

wenden könnten, ... Diejenigen aber in den Mauern - jeder Fünfte

soll

geben Die Sühne für seine Brüder hier. Geht hinaus und verschwendet

und tötet!' --'O Sultan, verzeihen Sie Meine Rede, antwortete ein

Soldat - "aber wir fürchten Die Geister der Nacht, und der Morgen

nähert sich" ('But first, go slay the rebels--why return / The victor

bands?' he said, 'millions yet live, / Of whom the weakest with one word

might turn / The scales of victory yet;--let none survive / But those within

the walls--each fifth shall give / The expiation for his brethren here.--

/ Go forth, and waste and kill!'--'O king, forgive / My speech,' a soldier

answered--'but we fear / The spirits of the night, and morn is drawing

near)" [53]

Aus dem Morgenland

kam ursprünglich alles Gute, das Christentum z.B.; heute kommt aus

dem nahen Osten die alles verpestende islamische Lehre in Form der Türken;

sie rollt über das "todverschmutzte Land (rolled over the death-polluted

land). Es kam Aus dem Osten wie Feuer (it came Out of the east like fire)...

ein verrottender Dampf Von den unbegrabenen Toten, unsichtbar und schnell

(a rotting vapour passed from the unburied dead, invisible and fast)."

Zudem brachten die Türken die Pest. "Dann kam Pest auf die Tiere ...

In ihren grünen Augen leuchtete eine seltsame Krankheit, sie sanken

in abscheuliche Krämfe, oder Schmerzen schwer und langsam (then Plague

came on the beasts ... In their green eyes a strange disease did glow,

they sank in hideous spasm, or pains severe and slow)." Alle Tiere würden

vergiftet: "Die Fische wurden in den Bächen vergiftet; die Vögel

verendeten in den grünen Wäldern; das Heer der Insekten verstummte;

das verstreute Vieh und die Herden, die die Jagd der wilden Bestien überlebt

hatten, starben und stöhnten, jeder auf dem Gesicht des anderen In

hilfloser Agonie; rund um die Stadt weinten die ganze Nacht, die schlanken

Hyänen wie hungernde Säuglinge (The fish were poisoned in the

streams; the birds / In the green woods perished; the insect race / Was

withered up; the scattered flocks and herds / Who had survived the wild

beasts' hungry chase / Died moaning, each upon the other's face / In helpless

agony gazing; round the City / All night, the lean hyaenas their sad case

/ Like starving infants wailed; a woeful ditty!)" [54]

Die Erkennungszeichen

bzw. "Zeichen des kommenden Unheils (signs of the coming mischief)" des

türkischen Islam waren Minarette (Minarets), wie sie heute sogar in

Europa von türkischen Terrororganisationen aufgestellt werden dürfen,

und ein "stimmloser Gedanke an das Böse, der sich verbreitete (A voiceless

thought of evil, which did spread)" sowie der "Lügenglaube", Pest,

das abchlachtten Unschuldiger, kurz: eine "schreckliche Brut (lie Faith,

and Plague, and Slaughter, A ghastly brood)." Auch Hungersnot ist ein Erkennungszeichen

des Islam bzw. der Eroberung durch die Türken: "Es gab keine Nahrung,

der Mais wurde zertrampelt, Die Schafe und Herden waren umgekommen (There

was no food, the corn was trampled down, / The flocks and herds had perished)."

Am Ende stand immer die Seuche: "Dann fiel blaue Pest auf die Rasse des

Menschen (Then fell blue Plague upon the race of man.)" [55]

Die katastrophalen

Folgen des islamischen Glauben wurden zunehmend auch den Fürsten bewusst:

"Die Fürsten und Priester waren blass vor Schrecken; Jener ungeheuerliche

Glaube, mit dem sie die Menschheit regierten, fiel, wie eine Welle, die

durch den Fehler des Bogenschützen gelöst wurde, auf ihr eigenes

Herz zurück: sie suchten und konnten Keine Zuflucht finden - es war

der Blinde, der die Blinden führte! Also, durch die trostlosen Straßen

zur hohen Moschee, winden sich die vielzüngigen und endlosen Armeen

in trauriger Prozession: jeder unter dem Zug zu seinem eigenen Idol hebt

seine Flehen vergeblich. (The Princes and the Priests were pale with terror;

/ That monstrous faith wherewith they ruled mankind, / Fell, like a shaft

loosed by the bowman's error, / On their own hearts: they sought and they

could find / No refuge--'twas the blind who led the blind! / So, through

the desolate streets to the high fane, / The many-tongued and endless armies

wind / In sad procession: each among the train / To his own Idol lifts

his supplications vain)." Zumal vom Islam auch kein Seelenheil zu erwarten

ist, weshalb das "Glaubensbekenntnis des Islam (Islam's creed)" oft als

"verabscheuungswürdig (detested)" bezeichnet wird. [56]

Wie könnte ein

vom islamischen Glauben Zerrütteter aussehen? "Nicht der Tod - der

Tod war keine Zuflucht oder Ruhe mehr; nicht das Leben - es war Verzweiflungzuspruch!

Nicht Schlaf, denn das waren Feuergründe und Feuerabgründe. Zu

dem die Zukunft, ... wie eine Geißel, oder wie ein Tyrannenauge,

das auf seine Sklaven blickt, ... sie hörten das Gebrüll der

schwefelhaltigen Welle der Hölle (Not death--death was no more refuge

or rest; / Not life--it was despair to be!--not sleep, / For fiends and

chasms of fire had dispossessed / All natural dreams: to wake was not to

weep, / ... Or like some tyrant's eye, which aye doth keep / Its withering

beam upon his slaves, did urge / Their steps; they heard the roar of Hell's

sulphureous surge)." [57]

Was könnte islamischen

Herrschern und Sultanen ins Stammbuch geschrieben werden? "Ihr sitzt inmitten

des Ruins, den ihr selbst gemacht habt, Ja, die Verwüstung hörte

den Knall deiner Trompete, und aus dem Schlaf ! Dunkler Terror hat deinem

Gebot gehorcht (ye sit amid the ruin which yourselves have made, Yes, Desolation

heard your trumpet's blast, and sprang from sleep!--dark Terror has obeyed

Your bidding)" ... "Das Böse wirft einen Schatten, der so schnell

nicht vergehen kann (evil casts a shade, Which cannot pass so soon)" ,

und durch den Hass auf das Christentum entsteht "eine kranke Nachkommenschaft

(an ill progeny)" [58]

Im Vorwort zu seinem

Lyrischen Drama Hellas schreibt Shelley: "Wir sind alle Griechen. Unsere

Gesetze, unsere Literatur, unsere Religion, unsere Künste haben ihre

Wurzeln in Griechenland (We are all Greeks. Our laws, our literature, our

religion, our arts

have their root in Greece)." [59]

Zur englischen Orientpolitik

schreibt er: "Die Engländer erlauben ihrem eigenen Unterdrücker,

sich entsprechend ihren natürlichen Sympathien mit dem türkischen

Tyrannen, und ihren Namen zu brandmarken indem sie eine Allianz mit den

Feinden des Glücks, des Christentums und der Zivilisation eingehen

(The English permit their own oppressors to act according to their natural

sympathy with the Turkish tyrant, and to brand upon their name the indelible

blot of an alliance with the enemies of domestic happiness, of Christianity

and civilisation)." [60]

Zu Russland schreibt

er, sicher nicht ganz treffend, wie er auch Schwierigkeiten hat das Christentum

richtig einzuordnen: "Russland will Griechenland besitzen, nicht befreien;

und ist zufrieden mit den Türken, ihren natürlichen Feinden und

den Griechen, ihren Sklaven, wenn sie gegeneinander kämpfen, bis einer

oder beide in sein Netz fallen. Die kluge und großzügige Politik

Englands hätte darin bestanden, die Unabhängigkeit Griechenlands

zu schaffen und sowohl gegen Russland und den Türken; aber wann war

der Unterdrücker (England) großzügig oder gerecht? (Russia

desires to possess, not to liberate Greece; and is contented to see the

Turks, its natural enemies, and the Greeks, its intended slaves, enfeeble

each other until one or both fall into its net. The wise and generous policy

of England would have consisted in establishing the independence of Greece,

and in maintaining it both against Russia and the Turk;--but when was the

oppressor generous or just?)" [61]

Andere europäische

Länder wie Frankreich und Spanien seien bereits frei, die Welt warte

nur darauf, dass Deutschland sich von der Monarchie befreie. Solange Europa

mit sich selbst beschäftigt sei, können die Türken in Ruhe

Osteuropa tyrannisieren: "The Spanish Peninsula is already free. France

is tranquil in the enjoyment of a partial exemption from the abuses which

its unnatural and feeble government are vainly attempting to revive. The

seed of blood and misery has been sown in Italy, and a more vigorous race

is arising to go forth to the harvest. The world waits only the news of

a revolution of Germany to see the tyrants who have pinnacled themselves

on its supineness precipitated into the ruin from which they shall never

arise. Well do these destroyers of mankind know their enemy, when they

impute the insurrection in Greece to the same spirit before which they

tremble throughout the rest of Europe, and that enemy well knows the power

and the cunning of its opponents, and watches the moment of their approaching

weakness and inevitable division to wrest the bloody sceptres from their

grasp." [62]

Der Chor singt: Am

großen Morgen der Welt, der Geist Gottes mit Macht entfaltet die

Flagge der Freiheit über das türkische Chaos, die Pracht der

Freiheit glänzte: Thermopylae und Marathon, der geflügelte Ruhm

Auf Philippi halb beleuchtet, Wie ein Adler auf einem Vorgebirge. Es lebte;

und leuchtet von Land zu Land Florenz, Albion, Schweiz. Dann fiel die Nacht

(Türkenjoch); und, ab der Nacht, feurige Flucht: aus dem Westen kam

schnelle Freiheit, Gegen den Lauf des Himmels und des Untergangs. Eine

zweite Sonne in Flammen aufgesetzt, zu verbrennen, zu entzünden. Frankreich

aber löschte es nicht; von Deutschland bis Spanien Verachtet man die

Warnung des umkämpften Sturms. Griechenland, Krank vor Hungersnot

durch die Türken, braucht Freiheit; ihre Ruinen leuchten wie Orient

Berge verloren in den Tag; in den nackten Aufhellungen Von Wahrheit reinigen

sie ihre geblendeten Augen. Lasst die Freiheit gehen - wohin sie fliegt,

Eine Wüste oder ein Paradies: Lassen Sie die Schönen und die

Mutigen teilen ihre Herrlichkeit oder ein Grab. [63]

Chorus:

In the great morning

of the world,

The Spirit of God

with might unfurled

The flag of Freedom

over Chaos,

And all its banded

anarchs fled,

Like vultures frighted

from Imaus,

Before an earthquake's

tread.--

So from Time's tempestuous

dawn

Freedom's splendour

burst and shone:--

Thermopylae and

Marathon

Caught like mountains

beacon-lighted,

The springing Fire.--The

winged glory

On Philippi half-alighted,

Like an eagle on

a promontory.

Its unwearied wings

could fan

The quenchless ashes

of Milan.

From age to age,

from man to man,

It lived; and lit

from land to land

Florence, Albion,

Switzerland.

Then night fell;

and, as from night,

Reassuming fiery

flight,

From the West swift

Freedom came,

Against the course

of Heaven and doom.

A second sun arrayed

in flame,

To burn, to kindle,

to illume.

From far Atlantis

its young beams

Chased the shadows

and the dreams.

France, with all

her sanguine steams,

Hid, but quenched

it not; again

Through clouds its

shafts of glory rain

From utmost Germany

to Spain.

As an eagle fed

with morning

Scorns the embattled

tempest's warning,

When she seeks her

aerie hanging

In the mountain-cedar's

hair,

And her brood expect

the clanging

Of her wings through

the wild air,

Sick with famine:--Freedom,

so

To what of Greece

remaineth now

Returns; her hoary

ruins glow

Like Orient mountains

lost in day;

Beneath the safety

of her wings

Her renovated nurslings

prey,

And in the naked

lightenings

Of truth they purge

their dazzled eyes.

Let Freedom leave--where'er

she flies,

A Desert, or a Paradise:

Let the beautiful

and the brave

Share her glory,

or a grave. - Percy Bysshe Shelley, Hellas

Der türkische

Sultan Mahmud tritt auf und sagt zu den Janitscharen (The Janizars), nicht

er sondern sie selbst sollen sich bezahlen und zwar "mit christlichem Blut!

Gibt es keine griechischen Jungfrauen dere Schreie und Krämpfe und

Tränen sie genießen können? Keine ungläubigen Kinder,

die sie auf Speeren aufspießen? Keine Heerpriester nach diesem Patriarchen,

der die Türken verflucht hat? Geht! tötet sie, Blut ist der Samen

des Goldes. "Go! bid them pay themselves With Christian blood! Are there

no Grecian virgins Whose shrieks and spasms and tears they may enjoy? No

infidel children to impale on spears? No hoary priests after that Patriarch

Who bent the curse against his country's heart, Which clove his own at

last? Go! bid them kill, Blood is the seed of gold." [64]

Mahmud schwärmt

von seinem Lügenprophet und dem Islam: "Um deinetwillen verflucht

sei die Stunde, auch als Vater eines bösen Kindes, als der Orientmond

des Islam triumphierte vom Kaukasus zum Weißen Ceraunia! Ruine oben,

und Anarchie unten; Terror nach außen und Verrat im Inneren; Der

Kelch der Zerstörung voll und alle haben Durst zu trinken (For thy

sake cursed be the hour, Even as a father by an evil child, When the orient

moon of Islam rolled in triumph from Caucasus to White Ceraunia! Ruin above,

and anarchy below; Terror without, and treachery within; The Chalice of

destruction full, and all Thirsting to drink)" [65]

Auch Hassan schwärmt

vom Lügengott Allah und seinem Propheten, und wie die Moslems in der

Wüstenei herrschen, die Griechen abschlachten, Österreich auf

Seiten der Türken kämpft: "Die Lampe unserer Herrschaft reitet

immer noch hoch; Ein Gott ist Gott - Mahomet ist sein Prophet. Vierhunderttausend

Moslems, von den Grenzen Von äußerster Asien, unwiderstehlich,

wie volle Wolken beim Schrei des Sirocco; ... Sie tragen den zerstörenden

Blitz, und ihr Schritt Weckt Erdbeben, um zu konsumieren und zu überwältigen,

und zu herrschen im Ruin... Samos ist blutüberströmt;-- der Grieche

hat bezahlt. Kurzer Sieg mit schnellem Verlust und langer Verzweiflung.

Die falschen moldawischen Leibeigene flohen schnell und weit Wenn der heftige

Ruf von 'Allah-illa-Allah!'ertönte... Die Anarchien Afrikas entfesseln

Ihre stürmischen Städte des Meeres, Um in Donner zur Rebellenwelt

zu sprechen. Wie schwefelhaltige Wolken, halb zerschmettert vom Sturm,

fegen sie über die blasse Ägäis, während die Königin

Vom Ozean, gebunden auf ihren Inselthron, weit im Westen, sitzt und trauert.

Russland schwebt immer noch, wie ein Adler In einer Wolke, er könnte

in dem untrennbaren Kampf auf den Sieger stoßen; denn es fürchtet

Den Namen Freiheit, auch wenn es die Türken hasst. Aber Österreich

liebt dich als das Grab, liebt Pest und ihre langsamen Kriegshunde, mit

der Verfolgungsjagd kommen Sie aus Italien, Und heulen an ihren Grenzen;

denn sie sehen, der Panther, Freiheit... Wessen Freunde sind nicht deine

Freunde, wessen Feinde deine Feinde? Unsere Arsenale und unsere Waffen

sind voll; Unsere Festungen trotzen dem Angriff; Der christliche Kaufmann;

und der gelbe Jude Verbirgt seinen Hort tiefer in der ungläubigen

Erde. ... Wir haben einen Gott, einen Sultan, eine Hoffnung, ein Gesetz;

Aber der vielköpfige Aufstand steht Geteilt in sich selbst, und muss

bald fallen (The lamp of our dominion still rides high; One God is God--Mahomet

is His prophet. Four hundred thousand Moslems, from the limits Of utmost

Asia, irresistibly Throng, like full clouds at the Sirocco's cry; But not

like them to weep their strength in tears: They bear destroying lightning,

and their step Wakes earthquake to consume and overwhelm, And reign in

ruin. ... Samos is drunk with blood;--the Greek has paid Brief victory

with swift loss and long despair. The false Moldavian serfs fled fast and

far When the fierce shout of 'Allah-illa-Allah!' ... The Anarchies of Africa

unleash Their tempest-winged cities of the sea, To speak in thunder to

the rebel world. Like sulphurous clouds, half-shattered by the storm, They

sweep the pale Aegean, while the Queen Of Ocean, bound upon her island-throne,

Far in the West, sits mourning that her sons Who frown on Freedom spare

a smile for thee: Russia still hovers, as an eagle might Within a cloud,

near which a kite and crane Hang tangled in inextricable fight, To stoop

upon the victor;--for she fears The name of Freedom, even as she hates

thine. But recreant Austria loves thee as the Grave Loves Pestilence, and

her slow dogs of war Fleshed with the chase, come up from Italy, And howl

upon their limits; for they see The panther, Freedom, fled to her old cover,

Amid seas and mountains, and a mightier brood Crouch round. What Anarch

wears a crown or mitre, Or bears the sword, or grasps the key of gold,

Whose friends are not thy friends, whose foes thy foes?0 Our arsenals and

our armouries are full; Our forts defy assault; ten thousand cannon Lie

ranged upon the beach, and hour by hour Their earth-convulsing wheels affright

the city; The galloping of fiery steeds makes pale The Christian merchant;

and the yellow Jew Hides his hoard deeper in the faithless earth. Like

clouds, and like the shadows of the clouds, Over the hills of Anatolia,

Swift in wide troops the Tartar chivalry Sweep;--the far flashing of their

starry lances Reverberates the dying light of day. We have one God, one

King, one Hope, one Law; But many-headed Insurrection stands Divided in

itself, and soon must fall)." [66]

Doch das Blatt wendet

sich und die Moslems (Türken) werden von der griechischen Armee zurückgedrängt:

Die eine Hälfte der griechischen Armee machte eine Brücke mit

moslementoten... In Nauplia, Tripolizza, Mothon, Athen, Navarin, Artas,

Monembasia, Korinth, erheben sich die Griechen und greifen die Türken

ann ("One half the Grecian army made a bridge Of safe and slow retreat,

with Moslem dead... Nauplia, Tripolizza, Mothon, Athens, Navarin, Artas,

Monembasia, Corinth, and Thebes are carried by assault, And every Islamite

who made his dogs Fat with the flesh of Galilean slaves Passed at the edge

of the sword: the lust of blood, Which made our warriors drunk, is quenched

in death; But like a fiery plague breaks out anew In deeds which make the

Christian cause look pale In its own light. The garrison of Patras Has

store but for ten days, nor is there hope But from the Briton: at once

slave and tyrant, His wishes still are weaker than his fears, Or he would

sell what faith may yet remain From the oaths broke in Genoa and in Norway;

And if you buy him not, your treasury Is empty even of promises--his own

coin. The freedman of a western poet-chief holds Attica with seven thousand

rebels, and has beat back the Pacha of Negropont: The aged Ali sits in

Yanina a crownless metaphor of empire: His name, that shadow of his withered

might, Holds our besieging army like a spell In prey to famine, pest, and

mutiny; He, bastioned in his citadel, looks forth Joyless upon the sapphire

lake that mirrors the ruins of the city where he reigned Childless and

sceptreless. The Greek has reaped the costly harvest his own blood matured,

not the sower, Ali--who has bought a truce from Ypsilanti with ten camel-loads

of Indian gold.)" [67]

Die Türken bauen

auf die Zerstrittenheit der Europäer und hoffen auf Sieg: "Sieg! Sieg!

Österreich, Russland, England, und diese zahme Schlange, dieser arme

Schatten, Frankreich, schreien Frieden, und das bedeutet den Tod, wenn

Monarchen sprechen. Ho, da! bringt Folterzubehör, schärft die

roten Pfähle, diese Ketten sind leicht, passender für Sklaven

und Vergifter als für Griechen. Töten! Plündern! Brennen!

lassen Sie nichts zurück. (Victory! Victory! Austria, Russia, England,

And that tame serpent, that poor shadow, France, Cry peace, and that means

death when monarchs speak. Ho, there! bring torches, sharpen those red

stakes, these chains are light, fitter for slaves and poisoners than Greeks.

Kill! plunder! burn! let none remain)." [68]

Dazu singt der Chor:

"Die Tyrannen sollen die Wüste regieren, die sie gemacht haben; Lasst

die Freien das Paradies besitzen, das sie für sich beanspruchen ...

(Let the tyrants rule the desert they have made; Let the free possess the